#165: Costco – 900 Stores vs 10,000

Manage episode 432941688 series 3492247

Sol Price had and idea that he was not going to let go of. No matter how many times others tried to take it away.

Dave Young:

Welcome to The Empire Builders podcast, teaching business owners the not-so-secret techniques that took famous businesses from mom and pop to major brands. Stephen Semple is a marketing consultant, story collector and storyteller. I’m Stephen’s sidekick and business partner Dave Young. Before we get into today’s episode, a word from our sponsor, which is, well, it’s us, but we’re highlighting ads we’ve written and produced for our clients. So here’s one of those.

[ASAP Commercial Doors Ad]

Dave Young:

Welcome to The Empire Builders podcast. Dave Young here with Stephen Semple. And Stephen, shoot, just as you hit the button, I was compiling a list because Julie and I, we’ve got to go pick some stuff up and you reminded me about it.

Stephen Semple:

Glad I can help.

Dave Young:

Right? We have a Google Keep list. I don’t know if you use Google Keep. It’s just sort of a list software that you can share with other people. And so that’s where we keep our Costco list.

Stephen Semple:

Right.

Dave Young:

And it’s actually a Costco/Sam’s list, but we hardly ever pick up anything from Sam’s. Sam’s has some things that Costco doesn’t and vice versa. Anyway, we’re going to talk about Costco, to try to make a short story long.

Stephen Semple:

I hope we still have some listeners at this point.

Dave Young:

Right? Come on, we’re only a minute in, so I think we’re okay.

Stephen Semple:

Here’s the thing I find it’s really interesting about Costco. Today, they have basically almost 900 locations. They do like 243 billion in revenue. They have over 130 million members, and they have over 300,000 employees. They have a reputation of paying and treating employees very, very well, especially for a discount outlet. But to put in perspective, they do a little bit more than half the revenue of Walmart. But Walmart has like 10,000 locations. Costco is like 900.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Think about that volume that they do.

Dave Young:

Do. The product turn has to be amazing. Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

Unbelievable. It’s just mind-boggling. It’s just mind-boggling. And it’s really interesting to stand outside of Costco and just look at carts full of stuff. Nobody goes to Costco and buys two things, right? It’s just incredible. There’s some legal things that we need to talk about to really understand the history of Costco, because back in 1936, there was this Robinson-Patman Act that was passed and it prevented the discounting of goods below the manufactured list price. So when we see manufacturers list price, it used to mean something. And what it used to mean is you could not go below that price. And this was to protect manufacturers and small retailers, and you could not do large purchases at discounts. It didn’t matter how much you were buying, couldn’t go below that price. And in the 1960s, these laws started to change, but large retailers still resisted this idea of lowering prices, because they’d sort of gotten very used to that.

Along comes Sol Price, and it’s the early 1950s and he’s working as a lawyer in San Diego, and he has a client in a jewelry business that’s selling watches to non-profit member owned retail operation in LA called Fedco. And Fedco was a non-profit, like basically it was founded by 800 postal workers in LA, and they were leveraging the buying power to negotiate with distributors and eliminate store markups. And there was a membership fee. It was $5 for a lifetime membership for federal employees. And Sol visited Fedco and he noticed that the property was really similar to one that his mother-in-law had inherited in San Diego that sat empty. So he suggested the location to the client of his and his mother-in-law, and they agreed, and they opened under a different name instead of Fedco. They called it FedMart under the same formula, but it was open to all federal employees.

So it’s December 3rd, 1954, he opens FedMart. It’s only for federal employees leveraging the membership fee and membership, a whole idea allowed them to purchase goods at bulk rate and sell them back at a low price. It was $2 for a lifetime membership, and they started with jewelry, then added furniture, then added liquor. And there was resistance to the model at first because people are like, “Well, why do I have to pay to shop? This is crazy. I can shop for free in other places.” And so in the first three months, he’s really struggling. The idea is not taking on. Now, Jim Sinegal got to remember that Jim’s name because Jim comes back into this story later, this story has got a couple of twists and turns. So Jim Sinegal is an employee of his, and he pointed out that this location used to pump gas and the hookups and everything were still there. So he said, “Why don’t we pump gas?”

Dave Young:

Oh, okay.

Stephen Semple:

And the selling of gas does really well because of course, as you know, sell gas cheap, people are coming on a very regular basis. “Boy, while I’m here getting gas, why don’t I get these other things?” And it’s a brand new idea, gas being attached to a retailer. No one had done that before. So cheap gas is the hook. Things take off. Sales jumped over $4 million in the first year, in 1954, which is huge. And it’s actually four times what they were expecting. They were hoping to do a million. They ended up doing 4 million. So they start expanding in the Southwest, they do Phoenix, they do San Antonio as well as other stores in San Diego. And at the end of the 1950s, they have a million members. 1962, they’re at 10 locations, 2,000 employees, 82 million in sales.

Now Target and Kmart launch, discount retailers, no membership fee. So in 1963, Fedco, it opens a few stores without membership fees to test that, but set themselves apart from Kmart and Target what they decide to offer as groceries. And then they decide to do things at these crazy low margins like television sets. Then they started adding non-perishable food items. By the end of 1963, they’ve got 13 locations and they’re doing a million bucks in profit, and they go public to expand. Shortly after that, sales stall, innovation stalls, the board gets in the way of a lot of ideas.

Dave Young:

Sure.

Stephen Semple:

Now Hugo Mann is this retailer from Germany, and he has money to buy the company and take it back private. So he buys the company, takes it back private. And guess what happens? We’ve seen this story before. Who gets fired?

Dave Young:

He does.

Stephen Semple:

The founder, Sol, gets canned. We’ve seen this story over and over again. So now it’s the mid-’70s, there’s recession, uncertainty, inflation. And Jim Sinegal, remember Jim? Jim decides to leave as well.

Dave Young:

Okay.

Stephen Semple:

And they decide to do something together. They decide to start a new idea together. They decide to reach out to small business owners and retailers and learn from them. What do they need? And they discover there’s a gap, that they would like to buy in bulk. The membership stores have disappeared at this point. They’re all gone. And you got Target, Walmart, and Kmart as discount stores. So they decide to create this bulk idea, but again, going back to members only, but sell to retailers. So basically, they build a buying group. They sell at or close to cost, and the money’s being made on the membership. In June 12th, 1976, they launch Price Club, which is still not to Costco yet, Price Club.

And they convert an airplane hangar in San Diego. It’s like a hundred thousand freaking square feet and it doubles the largest old space that they have, and it’s this warehouse style, piled high, again, new idea, right? It’s a warehouse, not a store. Stuff’s piled high and it’s made to sell to small businesses. First year, they actually don’t do very well. They lose like $750,000. Jim leaves to do his own thing. So Jim parts, leaves Sol, but Sol decides to broaden the membership to other select professionals, school teachers, hospital employees, etc, and it explodes. By 1980, sales hit $150 million, and he’s expanded to three locations. But then along comes Sam’s Club, again, this whole battle, no membership fee. And he responds, no membership fee and is open to anyone. They’re doing this battle. And then guess what happens? Remember Jim Sinegal?

Dave Young:

Mm-hmm.

Stephen Semple:

Who started with him, joined him and then left? Well, Jim Sinegal decides to enter the space with Costco.

Dave Young:

Stay tuned. We’re going to wrap up this story and tell you how to apply this lesson to your business right after this.

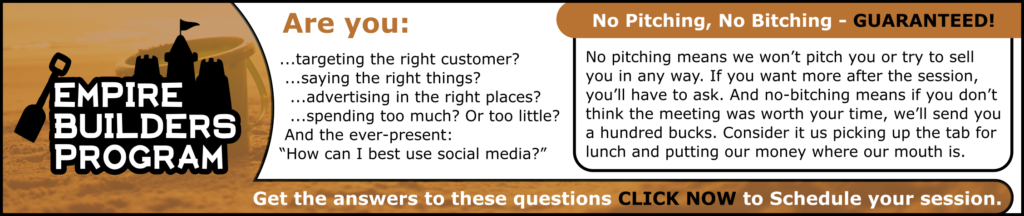

[Empire Builders Ad]

Stephen Semple:

So five years after leaving Price Club, he launches Costco. It’s 1984, he’s got three locations, they’re doing 100 million in sales, and it’s basically a copy of Price Club that he starts in Washington State, food, pharmacy, gas stations in an area with growing populations. But he stays with the membership idea. But anyone can get a membership. By 1985, he’s got 10 locations doing a billion. But then along comes 1993 and Jim and Sol makeup, and they merge, and it becomes Price Club. Originally, it was Price Club Costco, and then basically the Price Club part got dropped and it just is now the Costco that we know today.

Dave Young:

Interesting. That happened a year after I was married. So when we started, we were in a little rural place in Western Nebraska, and you could drive a couple hours to get to a Sam’s Club, but you couldn’t get to a Costco. I didn’t really fully experience Costco probably until about the time we moved to Tucson, which was a decade ago.

Stephen Semple:

It’s interesting when you think about 900 locations, it sounds like a lot until you compare it to other large retailers, like 900 locations is not… Yes, it’s huge, but at the same time, they’re not everywhere. They’re not in every location. But the part that I found that was very interesting is when we go back to the origin of this whole idea is these restrictions in place, you can’t do this or you can’t do that, these restrictions became an opportunity because the membership model allowed them to do things differently. It’s always really interesting when you see somebody who looks at a space and says, “Well, you know what? We could do it this way instead. We could do this membership model and it changes the way in which retail works.” It was a really interesting way of thinking and looking at retail and really changed the retail landscape. This whole concept of we don’t make our profit on the selling of the stuff. We make our profit on selling memberships.

Dave Young:

To be fair, they do make decent profit on the selling of goods. They’re not not making profit, they’re not losing money, they’re not selling at cost, but they’re turning their inventory 15 times a year or more. So when you’re not making huge margins, but you are turning your inventory, you’re just moving stuff through that store like gangbusters, the profits add up.

Stephen Semple:

Yes.

Dave Young:

And I had to look, because of course they’re publicly traded, but one of the things that I’ve seen, and you know more about the finance end of this than I do Stephen, but I think about large retailers that became publicly traded and left themselves open to these hedge fund guys that look at it and say, “Oh, well, you’re not returning enough profit to the shareholders.”

Stephen Semple:

Yes.

Dave Young:

Right? “So we’re going to take it over.” And when they do, they do things, they would change the whole Costco business model. They would say, “You’re not charging enough profit on these items, your retail sales, you’re probably leaving money on the table by not charging high enough membership fee. And you’re certainly, certainly overpaying your employees, and there’s way too many of them.” And so they look at the dollar bottom lines in all these areas. And if you change those things, Costco has it dialed in, customers are happy, happy, happy, happy. You change any of those three things, you’re going to tip the card over and you’re going to ruin what makes it great. And I’ve seen that happen with Cabela’s. I saw it happen with Toys”R”Us, right?

Stephen Semple:

Yes.

Dave Young:

They go in and do things that tip the apple cart over that put money in the pockets of the investors that don’t really belong there yet. They’ll saddle a company with debt, put that money in their pocket, they’ll fire the whole middle management of a company and put that money in the pocket of the executives and the shareholders. And when you destroy your customer experience, you lose the essence of it. And somehow, Costco’s managed to avoid that.

Stephen Semple:

And this is where it gets tough about people going, “Well, I want to measure the result of this and I want to measure result that.” And when you put your consumer hat on, let’s say Costco raised their margins a little bit, so they raised their margins a little bit. Let’s say they even raise their margins significantly. Well, you go, “Well, my membership renews once a year, so I’m going to still keep going. You know what? I’ll renew this once.” What ends up happening is these things while financially they hit the bottom line right away as a plus, and so therefore makes everybody feel like, “Oh my God, look, we had a record quarter. Look, we had a record quarter. We’re doing the right thing.”

On the other side, it erodes slowly. But here’s the problem. Once that erodes, it’s really fricking hard to get back. When you lose that customer, it’s very hard getting them back. It’s almost harder getting them back than it is getting them the first time. Because when you get them the first time, “I wonder what this is going to be like.” Getting them back is like, “I had a really crappy experience. I’m not going back.”

Dave Young:

Well, in the case of my Costco here, it’s like, well, oh, if they’ve raised prices, I’d probably come to the conclusion, “Well, there’s a Whole Foods right across the parking lot, and if I’m going to pay this price, I’m just going to get it from Whole Foods, and screw the membership.”

Stephen Semple:

And this is where measuring results can be very difficult, because even if you do something that’s positive, it can often take time for it to work its way through. It’s not like I do A and B happens right away. Sometimes, it does. Sometimes, it does. And we’re highlighting stories often where those things happen. But often, it’s slow change, slow change, and then hits that tipping point and takes off. But you’re right. Often, what happens, what comes in is these changes at our core DNA happen. And it’s amazing how often later those companies become only a former shell of their greatness, right? Because that decline happened slowly.

Dave Young:

I adore Costco. I love being one of their customers. I’ve never really met a cranky employee. They’re just careful about things and they’re paying attention to the things that matter, and they are not letting their eye off of that. Because they know that customer experience is such a lagging indicator. If people are unhappy today, it’s because of a decision that was made probably six months ago with hiring the wrong person, with buying the wrong thing, with pricing it the wrong way and doing your planning. The satisfaction is a result of things that happened some time ago.

Stephen Semple:

It’ll be very easy for the Costco experience to become a bad experience. The parking lot is crowded, the stores are big, the stores are crowded, you have to line up to pay, you have to line up again as you go out the door for them to check your receipt. It would be really, really easy for the Costco experience to become crappy, but for some reason, it isn’t.

Dave Young:

Yeah, I mean, even the longest line you’re in, you think, “Oh gosh, that looks really long,” but they somehow manage to speed right along. Again, they’ve trained us to know that’s part of the price. That customer experience is not… That’s a crowded store. We’re going to be in line a little bit. And if it gets too crowded, they’re going to open more lines. They’re pretty good at that. As opposed to places like a Walmart where not only do they not open new lines, but now, it’s just all machines anyway. It’s up to you to do-

Stephen Semple:

And the cashier greets you, as you said, with a smile. Yeah.

Dave Young:

Yeah.

Stephen Semple:

So anyway, there’s the story of Costco, and the nice part that I like is Jim and Sol made up at the end, and were now working together.

Dave Young:

Lives happily ever after.

Stephen Semple:

All right, thanks David.

Dave Young:

Thanks for bringing us to the Costco story, Stephen. Thanks for listening to the podcast. Please share us, subscribe on your favorite podcast app and leave us a big fat juicy five-star rating and review. And if you have any questions about this or any other podcast episode, email to questions@theempirebuilderspodcast.com.

179 episoade